LIFE AT BUTLERS - 08

Year 1953, and working at home

By Martin Edgar

8. YEAR 1953, AND WORKING AT HOME

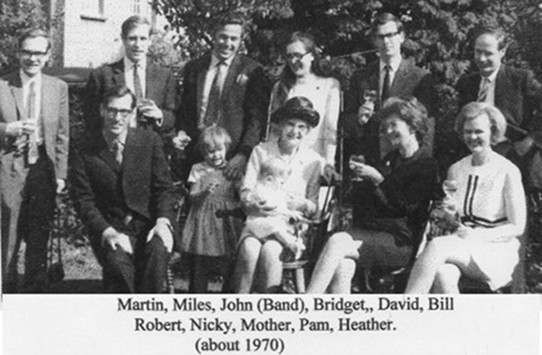

I left school at 17 with the general intention of being a farmer. We had generations of farming on both sides, so why not? Bill was running the farm at home, and Robert was doing his two years National service in the Intelligence Corps in Malaya. David and Miles were at Alleyn Court before themselves going to Felsted and Bridget was still at St Hilda's before going on to Queen Anne's at Caversham. As a necessary qualification for Writtle Agricultural College was a year's practical experience so that is what I started.

I started at harvest time. The corn was cut by the binder, which spat out string-bound sheaves of corn every 10 yards as it circled the field. As the uncut corn in the centre of the field got smaller and smaller, tension rose. We all knew that at some stage the rabbits which had been driven relentlessly into the centre by the encircling binder would break cover, and when they did, that was the opportunity for someone's free supper. So we waited, sticks in hand...

Apart from that, we worked in pairs, picking up a sheaf by its string, swinging it upright to drive the butt into the ground and resting the head of ears in its pair put up by your partner opposite. Three or four pairs standing together made up a stook. One guaranteed result was arms liberally covered with scratches from the hard ends of the corn stalks. The stooks of corn were left for a few days to dry, as one certain result from making a stack of wet corn is that it will go up in flames. Wet botanical material in bulk heats up - try your compost heap. I have a clear memory of a haystack going up some years before in the open ground by the Chase near Alfred Martin's cottage. The Fire Brigade came to do what they could (largely stopping it spreading), and there was much excitement, particularly for a young boy.

Back to harvest. It was a question of judgment as to when to cart in the corn - was it dry enough yet, is it going to rain tonight, has it been standing so long that the grain is starting to fall out of the ears? When the time is right, the wagons would be harnessed up, the elevator put in position in Stack Yard, and we would be off with a steady stream of horse-drawn wagons loaded ten feet or more high, bringing the loads of sheaves in to Stack Yard. You loaded a wagon much as you made a stack - fill the bottom, and then build round right to the edge first, with the butt end of the sheaf outwards, and packed down tight. Then fill the middle, binding in with the outer ring. That way you could get a high and remarkably stable load, so the person pitching the sheaves up to you had to go to the full length of his pitchfork. Then you were handed up the reins by the loader's pitchfork and started for home perched on the front of the load, hoping nobody had closed a gate in the meantime. It was the devil's own job if they had, sliding down from the top to open a gate, and getting back up again to start unloading in Stack Yard.

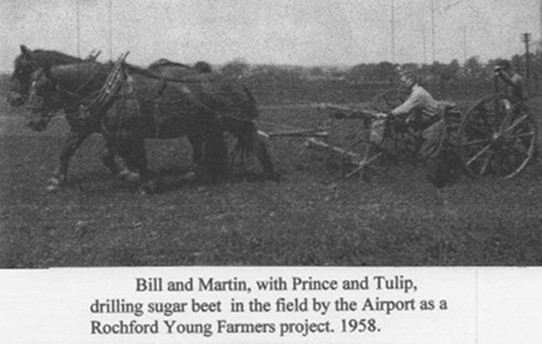

We had five horses on the farm - a pair of dark Shires with white hairy hocks, a mare and a gelding as always, called Mike and Mary. Mary's real name was Sutton Marcia and she was presumably locally bred. They were big horses and were Walter's horses before he became foreman, and then Pearce's as he took over as Head Horseman. Then there was a pair of chestnut Suffolk Punches, slightly smaller in height to keep the weight down for the heavier lands of East Anglia, but square and powerful all the same. These were big Jim Rippingale's, who had a bit of a taste for practical jokes, so you were a bit cautious with him. The gelding of that pair was a tall, rangy horse (for a Suffolk) by the name of Prince, who was a bit mad, and the quiet and gentle mare was Tulip. Finally there was a fat and rather lazy Belgian mare by the name of Smiler, who was prone to take unscheduled stops for a bite out of the nearest hedge or a mouthful of grass from the verge, and was not averse to having a bite out of you too if she could. She was wholly incorrigible.

Jim Rippingale also did the routine thatching on the farm, such as thatching the corn stacks, the hayricks and the potato clamps. The big jobs like re-thatching the barn or the stables were done by professional thatchers brought in.

I remember a couple of incidents with Prince. One wet spring we were carting muck from the cattle yards to spread it up on the fields. One horse could manage a loaded cart on the farm tracks, but on the wet field it was hard going. So Smiler was kept up the field as a trace horse, so that her chain traces could be hooked on to the front of the shafts, and two horses pull with Smiler in front of the shaft horse. I had Prince for my cart, and when I got up there and hooked up Smiler Prince was having none of this. He was determined to be first, and with enormous effort and much puffing set out to overtake Smiler. It was a bit tricky trying to control this lot - managing two pairs of reins and forking the muck off the back of the cart, all at the same time.

Then one summer evening, I was up the far end of the farm in Wood Field with Prince, and five o'clock came, knocking off time. I knew it and Prince knew it. So we turned for home, and then I heard a shot in the distance. So I stopped Prince, got off the cart and went across the field to see who it was. Prince wasn't going to wait, and started off for home. He shifted up a gear to a gentle trot, and then the noise of the cart behind him must have frightened him, and he was off, cart and all. He cantered (or galloped) through Bushy Bit, round the pond there, through the gate and turned right into the back lane past Cadge's, and so to the gate to Cow Meadow. There he had a problem; the gate was shut. So he did what any sensible horse would do, he tried to jump it. As I followed, I found the gate split in two and found Prince in the yard to the cow sheds, still in the shafts with an unbroken cart behind him, and breathing rather heavily. The next morning he was just a bit stiff.

It was routine on Saturday lunchtimes in summer that the horses would be put out to grass in Cow Meadow for the weekend. So the gate to the house would be closed, and the horses let loose from the stable. They would come out of the stable yard at an easy gallop, each horse weighing close on a ton, swing right to go through the Yard past the barn, round into Stack Yard, and you had to make sure that you had opened the gate in to Cow Meadow as they thundered through. There they would kick up their heels and roll on the ground to scratch their backs, before calming down and drinking deeply from the water trough. It was quite a sight.

Morning "Orders" would be at 7o'clock, and we all foregathered in the Stables. It was at least comfortable there with the smells of warm horse, fresh cut hay, oats and the sharper smell of horse dung. Bill would spell out the day's jobs, and he and Walter worked out who was to do what. Then we each got on with the day's task, initially until breakfast time at 8.30. Bill and I would go back to the kitchen for porridge, egg and bacon or whatever Mother had on that day, and as much toast and marmalade as could be crammed in for that half hour. Then back out into the outside world, and I would be hungry again by 11. Lunch was from 12.30 to 1.30, and we finally finished work at 5.

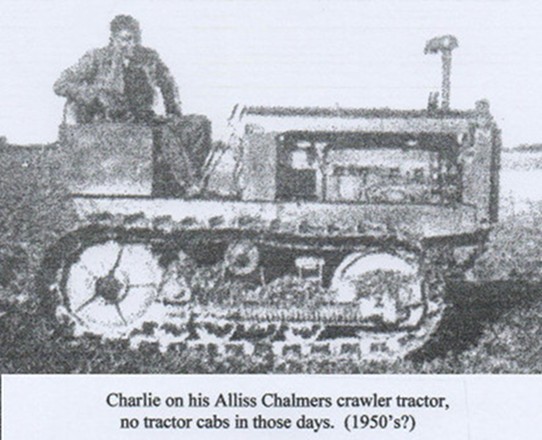

Once the harvest was in, it was ploughing time. We had three tractors for this; an Allis Chalmers crawler which was Charlie's pride and joy, a Fordson which had replaced a pre-war Case, and the small Ferguson. All three were paraffin fuelled, but you had to start with petrol as paraffin would not vaporize in a cold engine. After a while you switched over to paraffin; if you did it too early, you got a stopped tractor and a flooded engine.

Walter taught me to plough on the Ferguson, a neat tractor with a hydraulic lift three-furrow plough. I learnt that the key is to get your first furrow dead straight. So you would put up two sticks in line and 20 yards apart at the far end of the furrow you are going to plough. You then set yourself up so that the sticks are absolutely in line, and you keep it like that as you draw the furrow. There it is, dead straight. After that you keep the plough set to throw the furrows at an even height and so that all the stubble and weeds are turned upside down and out of sight. The land is then flat earth, even and not spoiled by a whisker of vegetation. A major sneer when someone's plough was not set right was "He hasn't buried all his rubbish."

I thought I became quite a dab hand at ploughing, and wouldn't have minded having a go at the local ploughing match but that was Charlie's privilege. He used to take the Allis Chalmers and a four furrow trail plough (it had no hydraulic lift). He never won first prize, but did manage an occasional second or third. Walter sometimes entered the horse class to plough his statutory acre; they say an acre is defined as the land one horse can plough in a day. Horse ploughing is not easy. You have to keep the plough balanced, and so need both hands on the handles. At the same time you have to control your pair of horses and therefore hold the reins as well. To make things even trickier, walking is uneven with one foot in the furrow and one foot on the land, all at the same time. So words of command have been developed. "Giddup" and "whoa" are well known; what are less well known are "coup" (or "cup") for go left (usually said twice or three times) and "wooorgee" for go right.

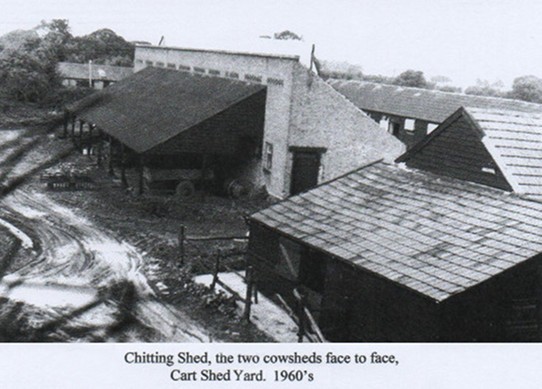

As we moved into autumn, it was time for the main crop potato harvest, either the red King Edwards or the heavier cropping (but cheaper priced) white, Majestic. First of all, Bill would go and collect the "'Tatey Gang" from the estate by the Anne Boleyn - half a dozen women who liked to earn a bit of extra money. They were quite a feisty lot, led by Iris, an irrepressible character. They were no respecters of persons, and would strip off to bra and skirt in the warmer weather, which was quite a surprise to a young teenager fresh out of school. The rows of potatoes would be spun out of the ground by a spinner mounted on the back of the Ferguson, and the Gang would work their way up the field picking up the potatoes and putting them in the potato trays (also used for chitting later in the winter). These would be collected by horse and cart, taken back to near the farm buildings where they were going to be stored in a potato clamp - a pile of potatoes five feet high and 20 yards long. We would have a motorised riddle there so that clods of earth and tiny potatoes could be picked out and the good stuff piled in the clamp. This would then be thatched with straw to keep the frost out. As and when the market was right at any time through the winter, the clamp would be broken open and potatoes bagged up in hundredweight (112lb) bags. These would be collected, usually about 6 tons, by a lorry from West's the vegetable wholesalers in Southend. You were always careful to keep count of the bags that went on the lorry, as otherwise you might find the official tally was a couple of bags less than you thought...

Then we were into the winter vegetables. Depending on need and season, we would be cutting curly kale, cauliflowers, January King cabbages or picking sprouts, and bagging them up tight in hessian sacks for West's to come and collect in six ton loads. This was done in all weathers, and a bit of rain made no difference. It didn't matter if you were wet, so long as you kept warm. A fairly common method of keeping the worst off was to make a hood out of a hessian sack, throw it over your head and shoulders, and you finished up looking like an agricultural monk. Then by early spring we would be into spring greens.

Come the spring the tempo changed. The drill would be in regular use, putting in seed in lines up the fields. That was fine for corn, but the line of new vegetable seedlings would need singling out quite early. So three or four of us would go out in a line across the rows, each armed with a hoe, and take the seedlings down to one plant every foot or so. It was a quick chop to the left and a quick chop to the right, then with the flat of the hoe push out the last rejects close in to the seedling chosen to remain. The rows seemed to go on for ever and it was hell for the back.

The potatoes would be planted out and the rows banked up. We would start with the earlies (Arran Pilot), which would be planted in April and harvested in June, and follow with the others. Father had always bought Scottish seed potatoes on the basis that after a tough upbringing up there they would do well down south. By June we would be watching the farming press to see how the Cornish and West Country harvests of early potatoes were developing, as they were earlier than we were. Since the yields for earlies were low, so the premium you got for being among the first on the market paid real dividends.

The threshing of the corn stacks would generally be deferred to late winter or spring when better prices were to be had. The threshing gang would arrive, with the big steam traction engine pulling the big, square, red painted thresher. The thresher would be set up tight against the stack, the traction engine lined up so that the belt from its big flywheel would drive the thresher, and it would start in a cloud of dust. Our men would pitch the sheaves of corn from the stack into the top of the thresher, and the threshed corn would flow out of the bottom into large 16 stone sacks. The sacks were then taken over to the barn and stacked inside there. It was surprising how much you can carry, if you do it right. I was 5'6" and hardly weighed 10 stone. Yet I carried one as an experiment, and it was quite easy. Just stand up straight and put the sack high on your back so that the weight goes straight down a vertical back and straight legs to the ground. They always said that carrying weights was more technique than strength.

The threshed straw came shuffling out of the back of the thresher into a bailing machine, which compressed the straw into 4 foot by 2 foot bales by a long arm which steadily rose and fell with the regularity of a metronome. The bales were tied automatically by string and we then stacked them for use later for bedding in the stables and yards.

Again there was excitement when the corn stack was reduced to the last few feet. Suddenly the rats and mice which had been living in the stack would make a dash for it, and everybody would down tools to pursue them stick in hand.

Then it was into the summer maintenance: spraying the corn with selective weed killer (2-4D, long since outlawed), and regularly going through the fields of vegetables keeping them clean of weeds. Bill usually kept one field of pasture for hay, so when that had grown up and was ready it would be cut and regularly turned until dry enough to stack.

An early summer crop was a pea crop that we used to grow under contract with Birds Eye. As the pods started swelling a sharp eye would be kept on them. When Birds Eye judged it right they would set up a freezing plant a couple of miles away, sometimes at Stambridge Mills. The crop would be cut and loaded, haulm and all, onto a series of lorries which shuttled to and fro to the freezing plant. Birds Eye always used to say that their peas were frozen within four hours of harvesting, and as far as I could see they were right.

There were plenty of birds in those days. Swallows nested in the stables, the garage at the back of the house and in the barns and some house martins built their mud nests under the eaves of the house. There were also a few swifts. The place was heaving with sparrows and there were the usual robins and wrens. A tree creeper and nuthatch were seen regularly, particularly on the sycamore at the back of the house outside the bathroom window - the best view point. Wood pigeons were a menace, particularly in gobbling up young green stuff in the fields where they could do considerable damage. And turtle doves were around but there were absolutely no collared doves. Green woodpeckers would come anting on the lawn in front of the house. There would be the partridges and very occasional quail in the corn fields, and the hedges would have their yellow-hammers (yellow buntings) singing "a little bit of bread and no cheeeeze" from the top branches, plus the occasional flock of goldfinches. Blackcaps were seen in the hedges in the spring. Peewits (lapwings) would be fairly common in the fields, as would skylarks. There was a rookery in the trees at the end of the garden, and of course we would have some crows, magpies and the occasional jay around, which we shot if we had the opportunity as they took eggs and young birds. The few little owls would also be shot if we got close enough, which we rarely did as they took eggs too. At least that is what we thought, though it is now established that they feed generally on beetles and small mammals. Barn and tawny owls were welcomed whenever seen, particularly for their mousing ability. There was even excitement when a woodcock was seen in the Wood. A few pheasants were there too.

In about 1954 Bill bought the combine harvester, which meant a change in operations as corn would now be come back to the farm in bulk in tractor drawn trailers, and then be stored inside the barn in large silos. So I was given the job to make a large opening in the end of the barn and building a pair of doors 10 feet wide. This was so that a trailer could be backed up close to the barn, emptied into a pit just inside the doors and the grain then be lifted by an elevator into the storage silos in the barn. The doors took me a while, and when it came to screwing in the hinges to the main timbers (centuries old oak), special measures were called for with doors of that size and weight. Rather than screws I used 6" coach bolts, which have a square head for a spanner rather than a slot for a screwdriver. I drilled out the oak with a hole the size of the bolts less only the width of the thread. Then I put a spanner on the bolt, but it would not move. It was only when I put a second spanner on the end of the first, so doubling the leverage, that I could get the bolt home. The old oak was that hard. This magnum opus is, I am glad to say, still there today, almost sixty years later.