LIFE AT BUTLERS - COMPLETE ARTICLE

Martin Edgar's Story

By Martin Edgar

Go directly to the Comments section

1. HOW WE GOT THERE

The Edgars came from Cumberland, though to be more exact, it was from the country just outside Keswick. The church registers of Crossthwaite Church show them living in the area back to the 1600's. Latterly they were tenants of Ormathwaite Farm, just next door to Ormathwaite House, with a fine view across the valley floor to Derwent Water, and with the fells of Skiddaw rising up behind. That was sheep country, where my father, Henry Edgar ("Harry"), (born there in 1887) was brought up and got to know his sheep. Like those of his time, he walked the two miles or so to school and back again, and finished schooling at 13.

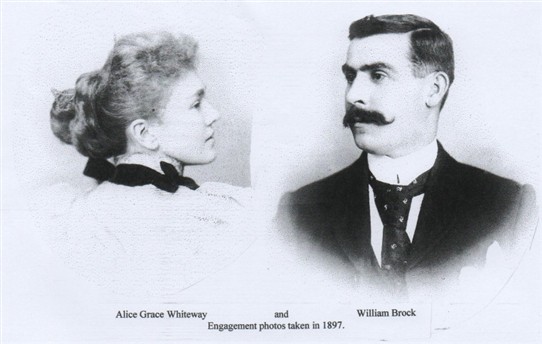

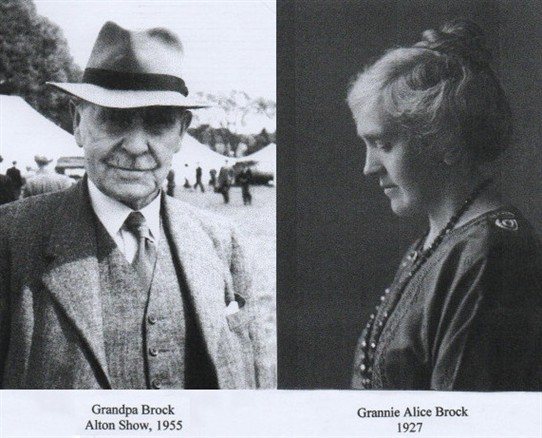

The Brocks were similarly a farming family, and were long established in Devon, between Exeter and Dartmoor. Latterly they had Holloway Farm at Kenn, a few miles down the Plymouth road from Exeter, where Grandpa William Brock was born in 1870. In about 1898, he married Alice Grace Whiteway, the daughter of the millers at Town Mills, Chudleigh, down the road. I have the photographs of each taken on the occasion of their engagement, and a handsome couple they look too. Rupert has the inlaid mahogany and ebony card table that was one of their wedding presents. William and Alice set out on the great adventure by setting up in Hampshire, and taking Pullens at West Worldham, near Alton. Their first child, my mother Grace Mary Brock, was born there in 1900. Liz has the set of four Regency chairs that were in the Morning (breakfast) Room at Pullens, just off the kitchen.

The moves to Hampshire were typical of the period. There had been a farming depression in the 1890s, particularly in the arable heartlands of England, largely caused by cheap imports of grain from Australia and Canada (shades of the Cutty Sark?). Farms could be rented at low rents, with perhaps a year or two rent free, so that the farms of the landed estates in the south were worked and did not fall derelict. Grandpa Brock took Pullens rent free for the first two years. These newly arrived sheep and cattle farmers from the north and the west were called "dog and stick farmers" by the Hampshire locals.

From Cumberland, the Edgars' friends, the Wrens, were first to come down. They found a place also in Hampshire, in the Meon valley, and sent word back to the Edgars that Old Place at East Tisted was available to rent. So the Edgars decided to take it and moved down by rail, including stock, over-nighting at Kings Cross, and on down to Hampshire. Grandpa John Edgar died in 1920, and Harry as the eldest son took over the running of the farm together with Grannie Isabella Edgar. So it was at the dances, tennis parties and visiting each others houses that Grace and Harry met in the 1920s, with West Worldham and East Tisted being only a few miles apart. They were sweethearts for quite a while until in 1930, when Harry had settled his siblings and handed over the running of Old Place to his youngest brother Harold. Harry married Grace at last and took Butlers Farm at Shopland, near Rochford in Essex, as tenant of the Tabor Estates and succeeding the Andrews. It would seem that the Andrews had been fairly severe masters, and it was probably something of a relief for the staff to have gentler hands on the tiller.

2. WHAT WAS THERE

If you came from Rochford on the Sutton road, fork left past Sutton and its early Norman church, and down the road to Shopland and Great Wakering, you got to Butlers after about two miles from Rochford. This was Essex marshes country, flat and open with the roads and hedges dotted with elm trees, and there was also the occasional small wood. Those elm trees which were such a feature have now all gone, killed by Dutch elm disease.

The farm was about 400 acres or more, going down to the Creek as we called it (actually the River Roach), where it was protected from flooding at high tide by the sea wall. Just on the far side of the sea wall was a small wharf, where (so we understood) Thames barges used to come down with muck from the London stables, and go back with cargos of corn. Beyond that, saltings stretched out to the middle of the river. You would see mallard, redshank, curlew, and shelduck regularly, and flocks of teal, widgeon and various geese would overwinter before returning to their breeding grounds in northern climes in the spring.

Part of the land inside the old sea wall was old saltings and pure clay, which we called "the Marsh" and was fit only for rough grazing. This was bounded on the farm side by the remains of an old sea wall, now just a low rampart and covered in bramble bushes, - and home to some badgers and plenty of rabbits. The rest of the farm was mostly fine brick earth, but some such as Cow Meadow was definitely on the clay side.

There was a fine four square Georgian house, built in about 1720, made with a timber frame (said to be old ships timbers) and white painted weatherboard on the outside. One result of this was that the house was always slightly on the move, and we always had draughts. Quite noticeable in the early days of no electricity and no central heating - we didn't get electricity until 1947. From the road there was a gravel drive, lined by daffodils in each spring. Mother had planted them. The drive then crossed the moat which went round two sides of the house and garden, and then curled round in front of the house and went through the gate to the farmyard at the back. A separate drive ("The Chase") ran from the road by a different route to the farmyard and farm buildings, for use by farm traffic.

The front garden consisted of a long lawn running down to the moat, with a handsome cedar tree to the far right, and Mother's herbaceous border running down on the left. The Shrubbery bordered the drive on the right, consisting of trees and some specimen shrubs, all very shady. The Little Garden round the corner of the house was a small lawn running to the edge of the moat (quite close to the house there) where there was an old garden shed. In fact, it was an old privy - a three holer, two adults and a child - built on the edge of the moat and to overhang it.

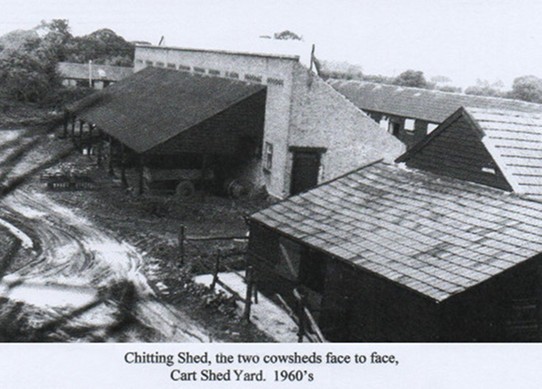

From the back door of the house, a path led down to the brick chitting shed, so called because seed potatoes were laid out on wooden slatted trays in winter, stacked on top of each other. The potatoes would start to sprout ("chit") before being planted out in April. That way, you got an earlier crop, and hopefully better prices. On the left of the path was a large Victoria plum tree. It was here that, during the War, we had the air raid shelter, a mound on top, dug down under two feet of earth. Inside there were two parallel tiers of bunk beds, sleeping four or six. I slept only a few nights down there, but it was quite exciting. On the right of the path was the apple orchard, with a mix of early (James Grieve), main crop (mostly Cox's Orange Pippins) and Bramley cooking apples.

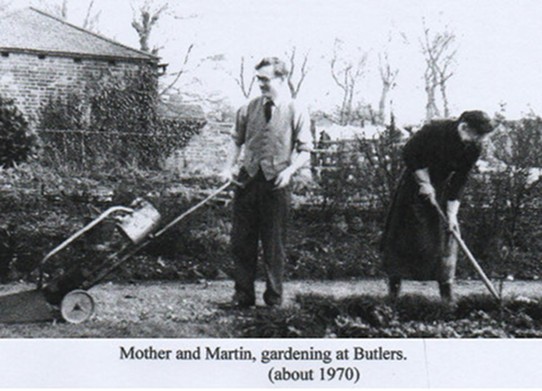

Behind the chitting shed was the kitchen garden, fenced off to keep the rabbits out. There were the usual vegetables, and quite a large walk-in cage of wire netting on posts, where the raspberries, redcurrents, blackcurrents and gooseberries grew.

The main farm buildings were:

A traditional great barn, probably centuries old. Bridget held her wedding reception there, all decorated with cut branches of flowering cherry and apple. We Young Farmers held occasional dances of a summer evening, with straw bales for seating.

Two brick cowsheds on opposite sides of their own rectangular yard, with a bull pen on the end of the far cowshed.

Then there were stables for eight horses, various sheds for tractors, two or three four wheeled wagons with their elegant lines and some two wheeled carts (all horse drawn), and farm machinery such as ploughs, a binder for cutting corn and binding it into sheaves, a drill for seeding land, a machine for breaking up cake for cattle feed, a riddle for grading potatoes and separating earth lumps, etc.

There were also the chitting shed and a separate smaller brick barn near the cowsheds where feed for the stock was kept. Out by the stables there were two smaller yards used for overwintering stock, particularly young heifers before they came into milk.

The big barn, the stables and associated yards and sheds were all thatched, which was replaced by asbestos sheeting in the 1960's. Ian has a late watercolour of these sheds in their thatched, but then rather dilapidated, state.

One relic of early days was an old shepherd's cabin - a large shed on wheels, tarred for weatherproofing, which could be taken out by horse and be overnight accommodation for the shepherd in lambing time. In fact all the wooden buildings, such as the great barn, used to be tarred every few years.

Opposite the great barn was an open space - Stack Yard, where there is a modern reinforced concrete barn these days. This was where the sheaves of corn were carted in by horse drawn wagon at harvest time, and stacks built, by pitching the individual sheaves from the wagon onto a mechanical elevator, from where they dropped onto the growing stack. There was a gang of three there, one at the bottom of the elevator (my job) to pitch the sheaf to the second in the middle, who pitched it on to the man (usually the foreman, Walter Cadge) working round the outside edge to make the stack. The trick was to start on the outside ring and get those firm and tight, butt end of the sheaf pointing out, and then fill to the middle while keeping the stack square, gradually building it out so that the bottom kept dry in the rain, and then bringing it in to make a sloping roof. That would then be thatched with straw.

The hen house was also in Stack Yard, home for a couple of dozen Rhode Island Reds. We had to shut them up every night in the hen house, as otherwise a fox would get them. Somebody forgot one night, and the carnage caused by a single fox has to be seen to be believed. We only kept the laying hens for one year, and then they went for the pot. New day old chicks would be bought, and sent to us in a cardboard box by rail, and we brought them on. We would get a phone call from Rochford Station that they had arrived, and would collect ours from a pile of cheeping boxes on the station platform.

The hayricks were put on the open ground beside the Chase just before you get to Alfred Martin's cottage on the bend. They were used for winter feed for the young stock in the yards. We used to cut squares out of them with a hay knife — about 30" long and quite wide with a cross handle at the top. So you set it vertical, and using your weight push it down and up to cut out the square of hay.

Just by the road, in the angle between the drive and the chase, there was a small wooden hut. This was the "mission", and home to one of those strange East Anglian non-conformist sects. I seem to remember that the Andrews had something to do with setting it up, or perhaps supported it. At any rate, most of the families on the farm went to it, and Walter Cadge became minister to the congregation, among his other responsibilities as Foreman on the farm.

3. EARLY YEARS

When Harry and Grace arrived there was no electricity but they did have mains water and drainage to a cess pit. I believe that there was a range in the kitchen which would have been the main source of hot water, and also a copper in the scullery for the weekly wash. Mother also had a paraffin (kerosene) stove with oven and two burners, which was kept in the scullery by the copper. There was of course no refrigerator. Food was kept cool on the slate shelves of the larder in the scullery, with an opening to the outside to let in cool air. Much effort was put into various forms of preserving, such as bottling fruit in Kilner jars, making jams and marmalades, preserving eggs in buckets filled with isinglass, etc. The apple crop would be carefully laid out on the slatted potato trays, no apple in contact with its neighbour to stop any rot spreading, and put down in the large cellar for winter supplies. For lighting we had an Aladdin lamp for the dining room, and quite a few brass oil lamps with their glass chimneys. They all burnt paraffin, and we did not really use candles. The Aladdin lamp had a woven fabric mantle over the wick, which burnt to ash on first lighting, but kept its shape. After that, the ash mantle would glow incandescently, and gave quite a good light, much better than the ordinary oil lamps.

By the beginning of the war in 1939 there were three children - Bill born in 1931, Robert in 1933 and me in 1936. We had a nanny (Hodgie) to help with the children, and I am sure Mother must have had help in the house with cleaning, etc. Running a family household was hard work in those days. My earliest memory is of standing in the kitchen with Hodgie, watching the Guy Fawkes fireworks outside. It must have been 1938, as the War started in September 1939 and there certainly would have been no fireworks then. Then there was being taken in a pram and sometimes walking, again by Hodgie, on the mile and a half walk to the Anne Boleyn and back. That also happened to be where the nearest bus stop was.

The heart of the house was the kitchen and the dining room - the kitchen because we had breakfast there on the scrubbed pine table and because it was warm, particularly after the range was replaced in the early war years by an AB, similar to an AGA. That was fired by anthracite, with which you filled a hopper so that the AB burned continuously. It was ideal to lean against and warm your bottom on a cold morning. The AB also provided constant hot water to the bathroom upstairs. There was no water in the kitchen, and all the food preparation was done in the scullery, which was where the washing up was also done. The scullery had a stone floor and a back door to the outside, so there was quite a contrast in temperature!

The dining room had a fire in the black marble Victorian fireplace - fires were not allowed in the bedrooms unless you were ill, a large mahogany table (now with Rupert) and chairs, and on the far side of the room a roll top desk where Father did his business. Thomas Brock now has the desk at Manor Farm, West Worldham. There were large alcoves on either side of the fire, with a built-in shelf in front of a bookcase on the left, and a bureau slope in front of another bookcase on the right, all in mahogany. The radio, battery powered by a car battery recharged weekly at Warrens the Garage in Rochford, was on the left hand shelf. This was the room where everything happened - the drawing room across the stairs was kept only for best e.g. the rather stiff teas when neighbours like the Penys from Paglesham or the Bentalls from Wakering came in. In winter, the Aladdin lamp would be on the table, with two oil lamps at each end of the mantelpiece. Mother and Father each had wingback chairs, and one boy would draw up another chair in front of the fire. The other two boys would sit on rush seated stools, one at each end of the fender with the front feet hooked over it, toasting the front of the body with the fire and with noses deep in books. You took care to be out of a draught. We consumed pages of Kipling, Arthur Ransome (e.g. Swallows and Amazons), and I read everything Felix Felton wrote (e.g. Bambi, etc), though I always skipped the last dozen pages as the books always finished in a tragic death. Or we would listen to the radio "Dick Barton - Special Agent" every night at 6.30, or the magazine programme "In Town Tonight" (sounds of traffic, it stops, "We stop the mighty roar of London's traffic to bring you . ."), or on Thursdays the comedian Tommy Handley in ITMA ("Its That Man Again"). In later years that was replaced by "Round the Horne" with its dreadful double entendres, or by Jimmy Edwards and the awful Glum family. Anything else was done on the dining table, whether playing Snakes and Ladders or Ludo, or doing hobbies. At one time I took up making model steam engines which you cut out of printed card and glued together, or I practised italic script which I rather fancied at the time.

4. THE WAR

When war broke out in 1939, the usual things happened. The windows were criss-crossed with brown paper tape, to stop glass flying around too much if the windows were blown in. The air raid shelter was dug out by the kitchen path, all the windows were covered by blackout material so that not a chink of light showed at night, and of course we each had our gas masks, to be carried at all times (a rule honoured more in the breach than in the observance). A few years earlier, tall lattice masts had been built at Canewdon, the early radar which proved so invaluable. You could see them from the attics at Butlers, looking north across the Creek to these half dozen oversize electricity pylons five miles away. The Army also requisitioned a field on the corner opposite Slated Row. Wooden huts went up, and gun emplacements were made for a battery of 3.7" anti-aircraft guns, with searchlights as well, and we called that the "Camp". Rochford airport was turned into a fighter aerodrome.

As we were near the mouth of the Thames, we could expect enemy bombers to pass overhead on their way to London, and you soon learned to tell them apart. Our planes had a steady note to the engines, but the enemy ones had a kind of throb. We also got used to the sound of the guns going off only two fields away, particularly at night, as we slept in the drawing room downstairs when the raids were at their peak. That was our main concession to events. It was even exciting to watch, with the searchlights sweeping the sky, and occasionally lighting up a bomber or pursuing fighters, and sometimes a solitary airman swinging on his parachute.

I was sent down to Hampshire for a couple of months during the height of the Battle of Britain, and stayed first with Uncle George and Aunty Margaret Joan at Manor Farm at West Worldham, then with the Baigents at East Worldham, and finally at Old Place where Aunty Ethel was living with Uncle Harold and his wife Sybil, and the dour and rather silent Grannie Edgar in her black bombazine. Aunty Ethel was good fun and we became friends, going for walks and collecting snails from under the wall while she gardened.

Life then settled down, and we got used to the rationing. We each had a ration book with coupons for meat, butter, etc. When you went to Shelleys the grocers or Fance the butchers in Rochford Square, the coupon for the week would be cut out and taken for the goods purchased. At one stage we decided to keep a pig, and had to surrender our meat ration in return. That pig produced the finest sausages I had ever tasted.

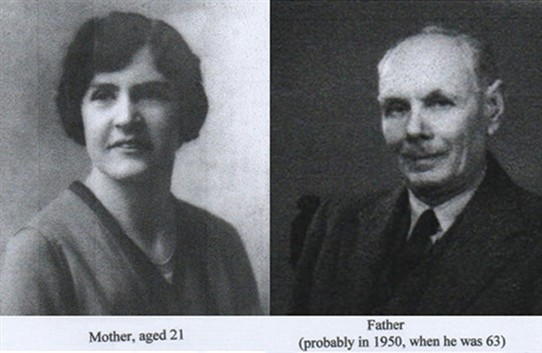

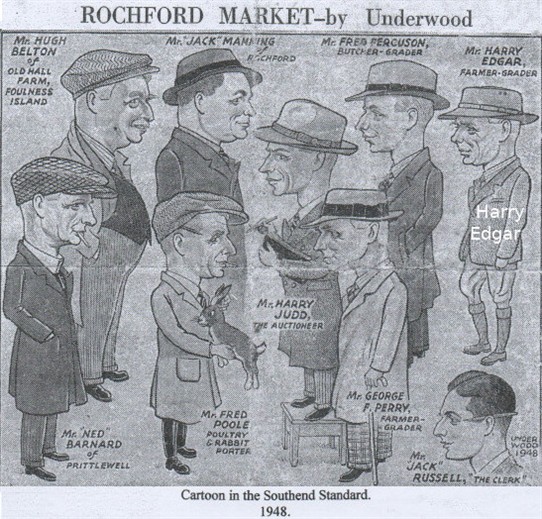

Rochford market still continued. Father was the official sheep grader, and would dress up to go to market, with breeches, well polished full length leather gaiters, jacket and tie. He made a dapper figure with his slight frame. He sometimes used to count his sheep in Cumbrian: yan, tyan, tethera, methera, pimp, sethera, lethera, hovera, dovera, dick. One to ten, if you haven't guessed. 15 was bumfit. I vaguely remember Father as a gentle and perhaps shy man as was Mother, though she projected a more stern exterior, and they both had high principles. It was a bit later that I discovered that Mother had a nice giggle when relaxed and comfortable in herself. Father was Churchwarden at Sutton church, and Mother followed him later in that role.

In 1941 I went to a kindergarten in Rochford in the mornings. It was in the back lane running behind the Square down to Warrens Garage. Mother would take me in first thing, and I would be collected by the milk float and brought home by the milkman for lunch. I clearly remember clip-clopping home in the summer sun, past the elm trees by the roadside and with one or two yellow-hammers singing in the hedgerow, since I was put to bed with sunstroke that afternoon.

We had a milk round in Rochford at that time - a pony and milk float carrying churns of milk and a pint measure. So customers had to provide their own containers, and the milk would be ladled into them by the pint. It was good creamy milk from our Shorthorn herd. Fance also delivered occasionally to us. They had a high-wheeled dogcart, smartly painted in cream and green, with a high stepping hackney pony in the shafts. It made a fine sight as it swept down the drive at a fast trot, and round in front of the house. Their butcher's shop in Rochford was very much in the old style, with the two Fance brothers doing the serving, and the rather fierce Miss Fance at the back in her cashier's cubicle - so that those handling meat did not handle money. Shelleys' on the corner of the Square was also the traditional grocers, with tiers of containers up the wall behind the counter. Individual requirements would be weighed out and put in brown paper bags, or if a small quantity put in a paper screw.

Then in 1942 I was six and went off to Alleyn Court School. Bill and Robert had already gone there. Alleyn Court had been a Westcliff school, but was evacuated down to Devon for the war. It had taken Bigadon House, a four square stone Georgian country house, some two miles outside Buckfastleigh. We would be taken up to Paddington station to join the school train, each carrying a small attaché case. Our clothes had already been packed into the big trunks and sent off by rail by Passenger Luggage in Advance a few days earlier. Mother would say goodbye and we boys would go to our allotted compartments - shades of the Hogwarts Express! Then there was the long journey down, but it got more interesting after we passed Exeter and travelled by the sea with its Brixham trawlers and other boats. We got off at Newton Abbott and boarded coaches (we were about 60 strong) to Bigadon, entering by the main gates and down the drive through laurel and rhododendron woods to the house, which stood on a high bluff some 200 feet above the main road below.

The house had no electricity, but it did have good central heating fired by coal and stoked by Walton the caretaker. So it was Aladdin lamps, oil lamps and candles. Chad (the Matron) was a small, fierce and energetic person, who went so fast down the corridors that the flame on her candle went down to just a red glow. We always wished for it to go out, but it never did. I visited Chad many years later, and found that she was actually a real softy. It was only when the chatter from the dormitory got to high decibel level that she would call out mock severely, "Stop talking, you boys." Rationing meant we had a tin of jam to last us the term, and we all manoeuvred to avoid the red jam. The marmalade was much better. Dried egg made up was a curiosity to be endured, but what we really enjoyed was the bread and dripping that Mrs Walton, the cook, brought out at elevenses. There was plenty of that, as it was off rations. There was always plenty to do, the staff were good and we enjoyed ourselves. So it was no great hardship to be away from home for most of the year, coming home for four weeks at Christmas and Easter, and eight weeks at harvest time.

Back home life continued on a pretty even keel. We were not much troubled by the actual war, at least as far as I remember, though William Cadge (always "Cadge" to us) lost two sons, both shot down in the Air Force. Hodgie had left to join up, and I did miss her for a while. Otherwise, life trundled on with the effects of wartime becoming normality.

At one stage the army put a solitary Bofors gun in Big Field, intending to catch any enemy bombers flying low up the Creek to get under the radar, but nothing came of it. One Heinkel bomber was brought down in Big Field, and was a ready source of the odd metal bits that small boys like to collect. If an incoming enemy bomber was really caught, it would drop its load of bombs and run for home. So we used to find the occasional unexploded incendiary bomb on the Marsh, and carry it home, swinging the 18" bomb from its fins. These were put in a shed, and the Bomb Disposal Officer used to drive over to collect them.

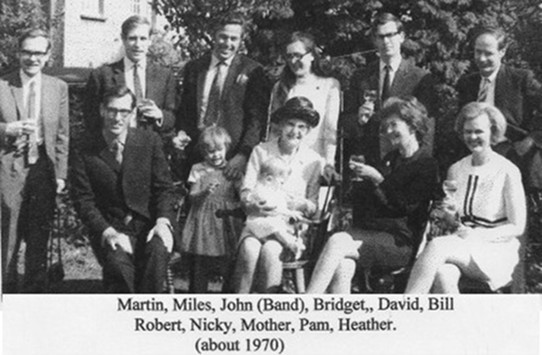

In 1942 the Twins were born. I remember Mother going off to a nursing home at Danbury for this birth, and it was novel to have these new bundles around. Then Miles was born in 1944, again I think at Danbury. It was not surprising that Mother should go away for the births. She was after all aged 44 by then, and had only had her first child at 31. She said that by the time you got to your sixth child, it was easy to cope - you just hung it on the line to dry...

5. PEACETIME

Alleyn Court returned to Westcliff in about 1947, but I continued as a boarder as I was well established and my friends were also boarders. At least it meant that I now got home at half term! David came as a day boy in about 1948, while Bridget went to St Hilda's just down the road. At home, Mother had acquired a Dutch au pair to help, Adri van Diss. She kept in touch over the years, even after she married an executive in Dutch radio at Hilversum. Beryl, the daughter of Hales, another of the men on the farm, came as a live-in help in the house. So in the holidays Mother and Beryl catered for 9 every day. As a reflection of the times (or perhaps pre-war attitudes), Beryl ate in the kitchen, and was summoned by an electric bell to collect the empty dishes and bring in the next course. At least we boys were sent to help with the washing up.

The spring of 1947 was bitterly cold, and I can remember snow drifts two or three feet high in the fields in the Easter holidays. In the summer of 1947, they brought electricity at last to Butlers. It was a delight to come home in July for the summer holidays, and turn on light with a switch. Then there were electric night storage heaters dotted round, which meant that we now had heating (of a sort as they were not all that efficient) in bedrooms and passage ways. The night storage heating was replaced by a hot air system that Bill and Pam put in when they moved to Butlers some 15 years or so later.

So life at Butlers was still holiday times only, where we mucked about and did all those things that boys do - potato fights in the chitting shed, draining water-filled ruts in the gateways in winter (we all became expert hydraulic engineers), being a nuisance to the cowman or any horseman who would put up with us, etc. Bill (then in mid-teens) had bought a brass cannon about 18" long and with a I" bore, the sort used by yacht clubs to start races. We used to cut open 12 bore cartridges, take out the powder and pour a teaspoonful in to the cannon, some more in the touch hole, and load with a missile. This could be a hardened potato, a bunch of nails or even the brass end to the cartridge. Point at a potato tray set upright 20 yards away and light the touch hole with a loud bang and a satisfactory cloud of smoke. The triumph was when we found a clear circular imprint in the wood with "Ely Kynoch" quite legible - a perfect reproduction of the cartridge end.

Eleven was the age when two important things happened:

Firstly, you got a bicycle for your birthday, and this opened up all sorts of new horizons. There were timed races home from Sutton Church, which was one mile (near enough), but we never managed to beat four minutes. That was the days of fairly heavy bikes and three speed Sturmey-Archer gears. Or friends such as David Lloyd, Jeremy Squier and Ian McCormick used to come over and we played games of bicycle polo in the Yard. It also meant that we could be sent into Rochford for the butter which had just run out, or go exploring the junk shops in Southend on our own. I built up a collection of Army cap badges, which could be had for a few pence each.

Secondly, Father taught me to shoot, and he took me up the fields to pepper with shot one of the concrete pillboxes in the centre of the farm. I started with the .410 (with its external hammers), and only graduated to the 16 bore or a 12 bore later. I still remember Father's basic rules:

Never, never let your gun

Pointed be at any one.

That it may not loaded be

Matters not the least to me.

When a hedge or ditch you cross,

Though it may of time cause loss,

From your gun the cartridge take

For the greater safety's sake.

The new game was therefore hunting rabbits or walking up hedgerows for pigeons. The main rabbit warrens were: in Cow Meadow by the small pond there; along the old sea wall; down at the Marsh; or in Bushy Bit. The best time was in the evening as the rabbits came out for their evening feed in the lengthening shadows. You would creep round, keeping low, trying to get within 30 yards (or preferably less) without disturbing them. Only the baby rabbits were spared. If you only wounded one, you had to kill it quickly and cleanly, and we became adept at that. Then it was back to home, where Mother had taught us how to gut, skin and prepare for the pot. I never did get to enjoy that bit very much. Reverting to war time, Mother had told us how to distinguish rabbit from cat, as they look almost identical skinned, and it was not unknown for cat to be sold. I believe the taste is quite similar. For information, only buy your carcase with the kidneys in. If it is rabbit, the kidneys are level; if cat, they are offset. Or the other way round - I forget.

One person who came round the farm fairly frequently was Les Cripps. Les lived out Great Wakering way, and had a fishing smack which he kept at Paglesham. It was said that Les was not always out for fish, and that perfumes and radios were another catch. We took care not to ask any questions, but there is no doubt that the creeks and inlets of the Essex marshes make it good smuggling country. Les had permission to shoot over the farm, so long as he took no game. So he mainly went for rabbits and pigeons, and of course looked to keep down the magpies and crows. He also came ferreting every now and then. You need a ferret and a number of small nets so that you peg nets over all the rabbit holes in a warren except one. You then put the ferret down that hole, and if you have the right warren, there will be a rabbit or two caught in the nets. You hoped that the ferret did not catch its prey under ground. If it did, the ferret stayed down to enjoy its meal, and you had to get your spade and dig it out.

Father also fulfilled a long held wish to have a really good gun. So he bought a second hand Holland & Holland (or was it a pair?), nicely cased, and went up to London to their shooting school to have some instruction, and to have the stocks of the guns adjusted to fit him. He also bought a good pair of binoculars, and was pleased with both purchases. We did not have a large amount of game on the farm, just a few coveys of partridge. These were mostly the grey partridge, or English as they are called, but also the odd covey of red-legged, or French, partridges. We also had a scattering of hares. But there was enough for Father to run an annual shoot in September with about half a dozen friends. The guns would take their stands as directed by Father (we boys did not shoot on the day), and the men would act as beaters walking up the fields towards us. There would be a whirr of wings as the partridges came fast and fairly low over us. As far as I can remember the bags were about a dozen or twenty brace of partridge, and a few hares. On one drive I was standing in a ditch beside Father, and as the birds came over, a neighbouring gun swung round to follow the birds - a major crime. I looked at the stick I was holding in front of me, and there was a pellet in it, just where it would have hit my forehead. The culprit went straight home, with hardly a word being said, he knew exactly what he had to do. No excuses, just go.

I also used to help with putting up the wages on a Friday. There would be small brown paper envelopes, pre-printed on the front for the name to be put in, the basic wage, and then additions and deductions, and of course a pile of cash. As far as I remember, the basic wage was about £5, with the head cowman, Pallett (who, with the other cowman, worked long hours as the cows needing milking first thing in the morning and again in late afternoon) and the foreman (Parminter, and then Walter Cadge) each getting £6. I think the Head horseman (Walter and later Pearce) and Charlie (Cadge) as Head tractor driver also got something extra. The extras would typically be for overtime, specially during harvest, and a normal deduction would be 6 shillings rent for those who had one of the farm's tied cottages.

Cadge lived in the cottage by the pond. He came to the farm in the Andrews time. I believe he was really a horseman and have vague recollection of his having been a jockey when young - he certainly had the small frame and bow legs that go with that job - but in Father's time became shepherd to the flock of 200 Suffolk sheep we used to keep. Father had to sell them shortly after the war, as they were largely kept in Hobbitt and the foot rot that sheep suffer from got into the ground. When a sheep's feet or teeth go, it is a goner and will starve. It has to keep on the move, grazing as it goes.

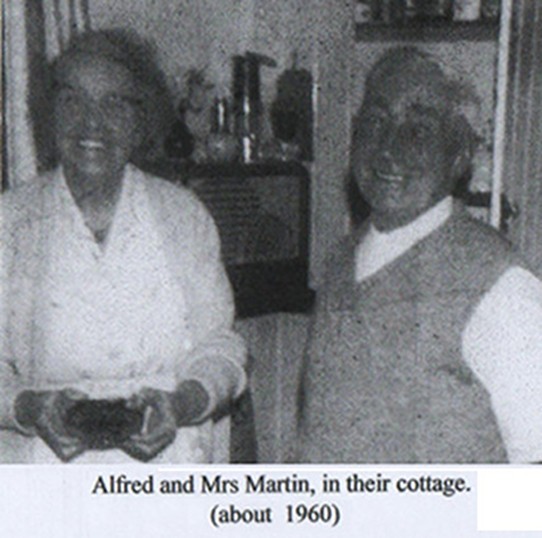

Then Alfred Martin had the cottage on the Chase as it turns the corner. He was a former miner, and had bicycled from South Wales in the 1930's Depression to find work. Mrs Martin was a ready source of comfort, tea and a good bun. Opposite the camp there was a semi-detached pair of houses, one for the Foreman (Parminter and then Walter) and the other for Pallett, the Head Cowman. Next door was Slated Row, originally a terrace of eight houses with outside privies. They were so small that I cannot imagine how people raised families in them. They were later converted into four terraced houses with kitchen etc extensions on the back. Amongst others, Charlie and Ruth Cadge lived there, and Ruth in particular became a great friend of the family, and a strong support to Bill and Pam in later years. I seem to remember that the total staff was about 13, which contrasts dramatically with the one and a half men that Bill finally ran the farm with forty years later.

I also used to help with the milk records. When Father gave up the sheep, he decided to go into dairy a bit more seriously. He must have sold the Shorthorns (though I cannot remember that being done), but I do remember his building up a herd of 60 Ayshires from the Reading sales. There was a feeling that the red and white Ayrshires were proper cows, unlike those black and white factory milk machines called Frisians which were then becoming fashionable. Alec Steel had a Frisian herd next door at Sutton Hall, and there were others about.

As I remember it, a good Ayrshire would produce milk with about 5% or 6% butterfat, whereas a Frisian's milk would only be about 3%. But on the other hand, a good Ayrshire would produce 6 gallons a day and a Frisian would clock up 8 (or was it 3 and 4?). Of course it helped that in those days milk with a higher butterfat commanded a premium price, which helped to redress the economic balance. Individual yields for each cow were meticulously recorded, both quantity and butterfat, so that the breeding programme could be managed properly and the quality of the herd improved. You hoped particularly for a heifer calf from your better cows. If it was a bull calf, it was weaned at four days old and sold for veal. We had our own bull for many years, but then artificial insemination came in and Father switched to that as it was cheaper and gave Father a choice of quality sires. By this time, the Rochford milk round had gone, and the milk was sold to the Milk Marketing Board whose lorry came every day to collect the churns from the Dairy loading dock.

6. CHRISTMAS

Christmas would follow a standard pattern. We came home from school in mid December, but Christmas did not really start until Christmas Eve. Then, the drawing room fire would be lit, and the Christmas tree put up in the corner by the far window. We all would decorate the tree, make decorations for the rooms, e.g. paper chains out of strips of coloured paper glued together, and would collect cuttings of ivy and berried holly to drape over the pictures and door casements of the drawing and dining rooms and in the front hall. A sprig of mistletoe would hang from the hall light. Then the presents would be put round the tree, and we would hang up socks for Father Christmas at the ends of our beds - even long after we knew who Father Christmas really was.

Grandpa Brock had long been widowed (Grannie Brock had died of skin cancer in 1930), and he came down from Worldham a few days before, together with Auntie Alice (his unmarried sister), and bringing the Christmas turkey with him. Auntie Alice kept house for him at Pullens. Where he was moustached and a bluff character, she was small with her hair screwed into a bun and a conspicuous wart on her nose. She spoke in a rather nice soft Devon accent, but had a slightly unfortunate air of disappointment about her.

Christmas dawned early, and we were eager to see what "Father Christmas" had brought. There were always a tangerine and a bar of chocolate, plus a few other small things. The family went first to the 8 o'clock service at Sutton church, and then came home to breakfast of hot porridge and hot boiled eggs or cold ham. Just as you were about to take the top off your nice boiled egg, there would be a scrunch on the gravel of the drive outside, and a couple of cars would draw up. It was the Salvation Army, about four or five bandsmen, and they would play us carols while we all stood freezing on the front door steps. Then Father would hand over a ten shilling note, and we boys would go down to try an experimental tootle on the trumpet or trombone, though we usually succeeded in making only rude noises. Then it was "Merry Christmas" all round. They would pile into the cars and be off to the next farm, while we went back to eggs now cold.

It was back to church again at Sutton, where Father was a Church Warden, for the 11 o'clock service, and then home to the usual Christmas lunch with Grandpa's turkey. But no presents yet - we had to wait until after the King's speech on the wireless at three o'clock. We usually got at least one book, possibly the latest Arthur Ransome, and the rest of the day could be spent devouring it in front of the fire. And then supper and finally bed...

7. YEAR 1950

I turned 14 and left Alleyn Court to go to Felsted on a classics scholarship. I was a ready learner and had been well taught. Bill had already been through Felsted - he was even there at the end of the war when Felsted had taken Goodrich Castle, on the Wye in Herefordshire and had just completed his year's course at Writtle Agricultural College. Robert was ahead of me at Felsted, where he was a house prefect. My scholarship was £100 a year, but Robert had won the top scholarship, also in classics, of £120. As we had also passed the 11 plus Father was paid £72 for each of us by the Government as we were not being educated at State expense. So nearly half of our fees of £400 each were paid for us.

Father was very ill with angina at the time, and we had to creep round the house quietly as we packed to go to school. Charlie drove us up there in farm pick-up, and then a week or so later I was called into the housemaster's study to be told Father had died. I don't remember Robert being with me - he must have been told separately. We then went home for the funeral.

The impression of the following weeks seems to be of a certain air of crisis. The key question appeared to be whether the Tabors would renew the tenancy. They did of course, but it had been by no means certain that a new tenancy would be granted to a 19 year old farmer and his widowed mother, with five dependants still to complete their education. The arrangements made were, I believe, that Uncle Jack (Baigent) would come down from Hampshire once a month to keep an eye on the farming, and that Grandpa Brock would guarantee the rent.

I certainly remember Uncle Jack's regular trip down. There was always a slight air of trepidation beforehand as he always seemed to expect things to be done well. He was a very successful and efficient farmer and shot clays for the English team, but in reality he was kind and helpful. The first thing he used to do on arrival was to go up to the Creek, for its extraordinary sense of peace, particularly of a summer evening. There would be this expanse of water (or mud at low tide) and the enormous bowl of sky overhead. You could see for miles. Hardly a bird stirred, and then a solitary redshank two hundred yards away would get up, fly a few yards, and settle again. Silence would return. We have all come back repeatedly to this haven of stillness.

8. YEAR 1953, AND WORKING AT HOME

I left school at 17 with the general intention of being a farmer. We had generations of farming on both sides, so why not? Bill was running the farm at home, and Robert was doing his two years National service in the Intelligence Corps in Malaya. David and Miles were at Alleyn Court before themselves going to Felsted and Bridget was still at St Hilda's before going on to Queen Anne's at Caversham. As a necessary qualification for Writtle Agricultural College was a year's practical experience so that is what I started.

I started at harvest time. The corn was cut by the binder, which spat out string-bound sheaves of corn every 10 yards as it circled the field. As the uncut corn in the centre of the field got smaller and smaller, tension rose. We all knew that at some stage the rabbits which had been driven relentlessly into the centre by the encircling binder would break cover, and when they did, that was the opportunity for someone's free supper. So we waited, sticks in hand...

Apart from that, we worked in pairs, picking up a sheaf by its string, swinging it upright to drive the butt into the ground and resting the head of ears in its pair put up by your partner opposite. Three or four pairs standing together made up a stook. One guaranteed result was arms liberally covered with scratches from the hard ends of the corn stalks. The stooks of corn were left for a few days to dry, as one certain result from making a stack of wet corn is that it will go up in flames. Wet botanical material in bulk heats up - try your compost heap. I have a clear memory of a haystack going up some years before in the open ground by the Chase near Alfred Martin's cottage. The Fire Brigade came to do what they could (largely stopping it spreading), and there was much excitement, particularly for a young boy.

Back to harvest. It was a question of judgment as to when to cart in the corn - was it dry enough yet, is it going to rain tonight, has it been standing so long that the grain is starting to fall out of the ears? When the time is right, the wagons would be harnessed up, the elevator put in position in Stack Yard, and we would be off with a steady stream of horse-drawn wagons loaded ten feet or more high, bringing the loads of sheaves in to Stack Yard. You loaded a wagon much as you made a stack - fill the bottom, and then build round right to the edge first, with the butt end of the sheaf outwards, and packed down tight. Then fill the middle, binding in with the outer ring. That way you could get a high and remarkably stable load, so the person pitching the sheaves up to you had to go to the full length of his pitchfork. Then you were handed up the reins by the loader's pitchfork and started for home perched on the front of the load, hoping nobody had closed a gate in the meantime. It was the devil's own job if they had, sliding down from the top to open a gate, and getting back up again to start unloading in Stack Yard.

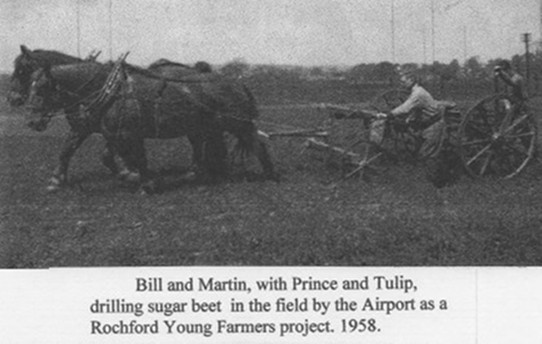

We had five horses on the farm - a pair of dark Shires with white hairy hocks, a mare and a gelding as always, called Mike and Mary. Mary's real name was Sutton Marcia and she was presumably locally bred. They were big horses and were Walter's horses before he became foreman, and then Pearce's as he took over as Head Horseman. Then there was a pair of chestnut Suffolk Punches, slightly smaller in height to keep the weight down for the heavier lands of East Anglia, but square and powerful all the same. These were big Jim Rippingale's, who had a bit of a taste for practical jokes, so you were a bit cautious with him. The gelding of that pair was a tall, rangy horse (for a Suffolk) by the name of Prince, who was a bit mad, and the quiet and gentle mare was Tulip. Finally there was a fat and rather lazy Belgian mare by the name of Smiler, who was prone to take unscheduled stops for a bite out of the nearest hedge or a mouthful of grass from the verge, and was not averse to having a bite out of you too if she could. She was wholly incorrigible.

Jim Rippingale also did the routine thatching on the farm, such as thatching the corn stacks, the hayricks and the potato clamps. The big jobs like re-thatching the barn or the stables were done by professional thatchers brought in.

I remember a couple of incidents with Prince. One wet spring we were carting muck from the cattle yards to spread it up on the fields. One horse could manage a loaded cart on the farm tracks, but on the wet field it was hard going. So Smiler was kept up the field as a trace horse, so that her chain traces could be hooked on to the front of the shafts, and two horses pull with Smiler in front of the shaft horse. I had Prince for my cart, and when I got up there and hooked up Smiler Prince was having none of this. He was determined to be first, and with enormous effort and much puffing set out to overtake Smiler. It was a bit tricky trying to control this lot - managing two pairs of reins and forking the muck off the back of the cart, all at the same time.

Then one summer evening, I was up the far end of the farm in Wood Field with Prince, and five o'clock came, knocking off time. I knew it and Prince knew it. So we turned for home, and then I heard a shot in the distance. So I stopped Prince, got off the cart and went across the field to see who it was. Prince wasn't going to wait, and started off for home. He shifted up a gear to a gentle trot, and then the noise of the cart behind him must have frightened him, and he was off, cart and all. He cantered (or galloped) through Bushy Bit, round the pond there, through the gate and turned right into the back lane past Cadge's, and so to the gate to Cow Meadow. There he had a problem; the gate was shut. So he did what any sensible horse would do, he tried to jump it. As I followed, I found the gate split in two and found Prince in the yard to the cow sheds, still in the shafts with an unbroken cart behind him, and breathing rather heavily. The next morning he was just a bit stiff.

It was routine on Saturday lunchtimes in summer that the horses would be put out to grass in Cow Meadow for the weekend. So the gate to the house would be closed, and the horses let loose from the stable. They would come out of the stable yard at an easy gallop, each horse weighing close on a ton, swing right to go through the Yard past the barn, round into Stack Yard, and you had to make sure that you had opened the gate in to Cow Meadow as they thundered through. There they would kick up their heels and roll on the ground to scratch their backs, before calming down and drinking deeply from the water trough. It was quite a sight.

Morning "Orders" would be at 7o'clock, and we all foregathered in the Stables. It was at least comfortable there with the smells of warm horse, fresh cut hay, oats and the sharper smell of horse dung. Bill would spell out the day's jobs, and he and Walter worked out who was to do what. Then we each got on with the day's task, initially until breakfast time at 8.30. Bill and I would go back to the kitchen for porridge, egg and bacon or whatever Mother had on that day, and as much toast and marmalade as could be crammed in for that half hour. Then back out into the outside world, and I would be hungry again by 11. Lunch was from 12.30 to 1.30, and we finally finished work at 5.

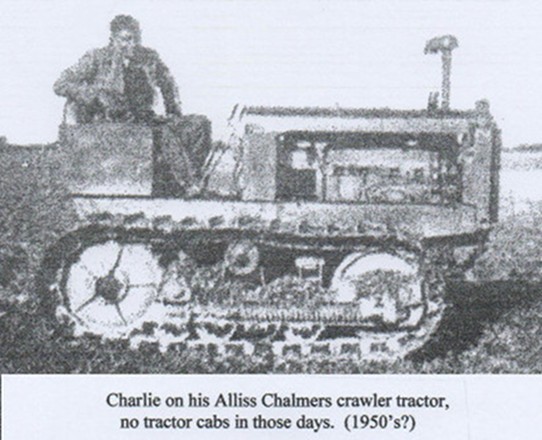

Once the harvest was in, it was ploughing time. We had three tractors for this; an Allis Chalmers crawler which was Charlie's pride and joy, a Fordson which had replaced a pre-war Case, and the small Ferguson. All three were paraffin fuelled, but you had to start with petrol as paraffin would not vaporize in a cold engine. After a while you switched over to paraffin; if you did it too early, you got a stopped tractor and a flooded engine.

Walter taught me to plough on the Ferguson, a neat tractor with a hydraulic lift three-furrow plough. I learnt that the key is to get your first furrow dead straight. So you would put up two sticks in line and 20 yards apart at the far end of the furrow you are going to plough. You then set yourself up so that the sticks are absolutely in line, and you keep it like that as you draw the furrow. There it is, dead straight. After that you keep the plough set to throw the furrows at an even height and so that all the stubble and weeds are turned upside down and out of sight. The land is then flat earth, even and not spoiled by a whisker of vegetation. A major sneer when someone's plough was not set right was "He hasn't buried all his rubbish."

I thought I became quite a dab hand at ploughing, and wouldn't have minded having a go at the local ploughing match but that was Charlie's privilege. He used to take the Allis Chalmers and a four furrow trail plough (it had no hydraulic lift). He never won first prize, but did manage an occasional second or third. Walter sometimes entered the horse class to plough his statutory acre; they say an acre is defined as the land one horse can plough in a day. Horse ploughing is not easy. You have to keep the plough balanced, and so need both hands on the handles. At the same time you have to control your pair of horses and therefore hold the reins as well. To make things even trickier, walking is uneven with one foot in the furrow and one foot on the land, all at the same time. So words of command have been developed. "Giddup" and "whoa" are well known; what are less well known are "coup" (or "cup") for go left (usually said twice or three times) and "wooorgee" for go right.

As we moved into autumn, it was time for the main crop potato harvest, either the red King Edwards or the heavier cropping (but cheaper priced) white, Majestic. First of all, Bill would go and collect the "'Tatey Gang" from the estate by the Anne Boleyn - half a dozen women who liked to earn a bit of extra money. They were quite a feisty lot, led by Iris, an irrepressible character. They were no respecters of persons, and would strip off to bra and skirt in the warmer weather, which was quite a surprise to a young teenager fresh out of school. The rows of potatoes would be spun out of the ground by a spinner mounted on the back of the Ferguson, and the Gang would work their way up the field picking up the potatoes and putting them in the potato trays (also used for chitting later in the winter). These would be collected by horse and cart, taken back to near the farm buildings where they were going to be stored in a potato clamp - a pile of potatoes five feet high and 20 yards long. We would have a motorised riddle there so that clods of earth and tiny potatoes could be picked out and the good stuff piled in the clamp. This would then be thatched with straw to keep the frost out. As and when the market was right at any time through the winter, the clamp would be broken open and potatoes bagged up in hundredweight (112lb) bags. These would be collected, usually about 6 tons, by a lorry from West's the vegetable wholesalers in Southend. You were always careful to keep count of the bags that went on the lorry, as otherwise you might find the official tally was a couple of bags less than you thought...

Then we were into the winter vegetables. Depending on need and season, we would be cutting curly kale, cauliflowers, January King cabbages or picking sprouts, and bagging them up tight in hessian sacks for West's to come and collect in six ton loads. This was done in all weathers, and a bit of rain made no difference. It didn't matter if you were wet, so long as you kept warm. A fairly common method of keeping the worst off was to make a hood out of a hessian sack, throw it over your head and shoulders, and you finished up looking like an agricultural monk. Then by early spring we would be into spring greens.

Come the spring the tempo changed. The drill would be in regular use, putting in seed in lines up the fields. That was fine for corn, but the line of new vegetable seedlings would need singling out quite early. So three or four of us would go out in a line across the rows, each armed with a hoe, and take the seedlings down to one plant every foot or so. It was a quick chop to the left and a quick chop to the right, then with the flat of the hoe push out the last rejects close in to the seedling chosen to remain. The rows seemed to go on for ever and it was hell for the back.

The potatoes would be planted out and the rows banked up. We would start with the earlies (Arran Pilot), which would be planted in April and harvested in June, and follow with the others. Father had always bought Scottish seed potatoes on the basis that after a tough upbringing up there they would do well down south. By June we would be watching the farming press to see how the Cornish and West Country harvests of early potatoes were developing, as they were earlier than we were. Since the yields for earlies were low, so the premium you got for being among the first on the market paid real dividends.

The threshing of the corn stacks would generally be deferred to late winter or spring when better prices were to be had. The threshing gang would arrive, with the big steam traction engine pulling the big, square, red painted thresher. The thresher would be set up tight against the stack, the traction engine lined up so that the belt from its big flywheel would drive the thresher, and it would start in a cloud of dust. Our men would pitch the sheaves of corn from the stack into the top of the thresher, and the threshed corn would flow out of the bottom into large 16 stone sacks. The sacks were then taken over to the barn and stacked inside there. It was surprising how much you can carry, if you do it right. I was 5'6" and hardly weighed 10 stone. Yet I carried one as an experiment, and it was quite easy. Just stand up straight and put the sack high on your back so that the weight goes straight down a vertical back and straight legs to the ground. They always said that carrying weights was more technique than strength.

The threshed straw came shuffling out of the back of the thresher into a bailing machine, which compressed the straw into 4 foot by 2 foot bales by a long arm which steadily rose and fell with the regularity of a metronome. The bales were tied automatically by string and we then stacked them for use later for bedding in the stables and yards.

Again there was excitement when the corn stack was reduced to the last few feet. Suddenly the rats and mice which had been living in the stack would make a dash for it, and everybody would down tools to pursue them stick in hand.

Then it was into the summer maintenance: spraying the corn with selective weed killer (2-4D, long since outlawed), and regularly going through the fields of vegetables keeping them clean of weeds. Bill usually kept one field of pasture for hay, so when that had grown up and was ready it would be cut and regularly turned until dry enough to stack.

An early summer crop was a pea crop that we used to grow under contract with Birds Eye. As the pods started swelling a sharp eye would be kept on them. When Birds Eye judged it right they would set up a freezing plant a couple of miles away, sometimes at Stambridge Mills. The crop would be cut and loaded, haulm and all, onto a series of lorries which shuttled to and fro to the freezing plant. Birds Eye always used to say that their peas were frozen within four hours of harvesting, and as far as I could see they were right.

There were plenty of birds in those days. Swallows nested in the stables, the garage at the back of the house and in the barns and some house martins built their mud nests under the eaves of the house. There were also a few swifts. The place was heaving with sparrows and there were the usual robins and wrens. A tree creeper and nuthatch were seen regularly, particularly on the sycamore at the back of the house outside the bathroom window - the best view point. Wood pigeons were a menace, particularly in gobbling up young green stuff in the fields where they could do considerable damage. And turtle doves were around but there were absolutely no collared doves. Green woodpeckers would come anting on the lawn in front of the house. There would be the partridges and very occasional quail in the corn fields, and the hedges would have their yellow-hammers (yellow buntings) singing "a little bit of bread and no cheeeeze" from the top branches, plus the occasional flock of goldfinches. Blackcaps were seen in the hedges in the spring. Peewits (lapwings) would be fairly common in the fields, as would skylarks. There was a rookery in the trees at the end of the garden, and of course we would have some crows, magpies and the occasional jay around, which we shot if we had the opportunity as they took eggs and young birds. The few little owls would also be shot if we got close enough, which we rarely did as they took eggs too. At least that is what we thought, though it is now established that they feed generally on beetles and small mammals. Barn and tawny owls were welcomed whenever seen, particularly for their mousing ability. There was even excitement when a woodcock was seen in the Wood. A few pheasants were there too.

In about 1954 Bill bought the combine harvester, which meant a change in operations as corn would now be come back to the farm in bulk in tractor drawn trailers, and then be stored inside the barn in large silos. So I was given the job to make a large opening in the end of the barn and building a pair of doors 10 feet wide. This was so that a trailer could be backed up close to the barn, emptied into a pit just inside the doors and the grain then be lifted by an elevator into the storage silos in the barn. The doors took me a while, and when it came to screwing in the hinges to the main timbers (centuries old oak), special measures were called for with doors of that size and weight. Rather than screws I used 6" coach bolts, which have a square head for a spanner rather than a slot for a screwdriver. I drilled out the oak with a hole the size of the bolts less only the width of the thread. Then I put a spanner on the bolt, but it would not move. It was only when I put a second spanner on the end of the first, so doubling the leverage, that I could get the bolt home. The old oak was that hard. This magnum opus is, I am glad to say, still there today, almost sixty years later.

9. END PIECE - CLAY SOIL AND WHAT TO DO

It is probably worth a word about the drainage works that Father undertook on the heavier land, such as Cow Meadow, either during or just after the war. He started off by mole draining. A steam traction engine would puff up the Chase and out to the field. It would have a winch on the back and would pull the mole drain itself. This was a bullet-shaped piece of steel about 2" in diameter, welded onto a 2 foot deep plate. The traction engine would be set up at one end of the field with the mole at the other, the winch cable would be laid out and the mole winched through the soil two feet down. It would leave a neat hole through the clay soil, which would keep open for a number of years. Repeat every 10 to 20 yards.

A more expensive, but more effective and permanent, solution which Father and Bill turned to was tile draining. Here, a 4" wide trench would be cut across the field and successive clay tile drains would be fed in, each about 3" in diameter and a couple of feet long. Repeat as above. Back fill, and you have a good drainage system.

An ancient method was to plough the land "on the stetch". You would open up the land as usual, first furrow one way and next furrow the other so that the soil was always thrown in towards the centre. You would carry on until the ploughed land was only 20 or 30 yards across, and of course the full length of the field. Then open up a new land. The following year, you would open up each land at exactly the same place. In this way, after a year or two, the field became a series of long raised beds with the intervening furrows acting as drains. The effect lasts a long time, and in a couple of fields we could still detect the gentle rise and fall in levels even though that field had been last ploughed on the stetch many years before.

A less effective cure for sticky and solid clay that Father tried was to spread the land with chalk (or possibly gysum). Apparently this changes the physics of clay in some way so that the fine particles of clay do not stick together so thoroughly. He did not try this much, so I suspect it did not work very well.

We did use gypsum for the East Coast floods. In 1950 a combination of a very high tide and strong easterly winds caused widespread flooding in East Anglia as the water came over the tops of the sea walls, and in many places the sea walls collapsed. Potton Island, Foulness and Canvey Island were totally flooded and their sea walls had large gaps, with the tides flooding in and out for several days. At Butlers, the tide just topped the sea wall but the wall held and only a few acres were flooded. But it did mean that this land was then contaminated by salt and normal crops would not grow on it. The cure was to treat the land with gypsum, which chemically neutralised the salt after a year or two.

10. YEARS 1954 to 1957

Then National service called and I went off in the Army to Germany for two years. Bill and Pam were married just as I returned, and started their married life in a caravan in the corner of Hobbitt up by the Mission. Butlers Gate was being built for them on the plot just across the Drive, in the corner of Drive Meadow that Mother had bought from the Tabors. Bill and Pam moved in after about a year.

As for myself, the thought of picking brussels sprouts with the ice on them had become less attractive and I had decided to become a Solicitor. I took up articles with my godfather, Ray Whiteway, in his Mayfair practice and the rest, as they say, is another story.

Martin Edgar, Richmond.

January, 2011.

11. POSTSCRIPT

This is a story of a childhood and growing up. But it is also two other stories as well.

First, it is a story of a place. Butlers has been there for a long time. I don't have accurate details, but I seem to remember that it is named after one William le Bottelier, who lived there probably in the 1300s. As Sutton Church is late 1100s or early 1200s, there must have been Norman settlements around here from those times, to justify the expense of putting up a good flint church. Then you have the moat, probably mediaeval and like other examples in East Anglia, which was more to provide fish and eels than for security. After all, it goes round only two sides of the house. The house itself was built in the early 1700s - again a fairly classic East Anglian design; timber-framed and with weatherboard cladding, which had to be painted every four years. As I remember it, the Tabors (as landlords) paid for the labour, and we paid for the materials. Being a timber structure, it tended to move and flex a bit, depending on the weather, with perpetual drafts as a result. So it was a chilly house, but if you were brought up in it you were used to that. The barn was probably mediaeval, and goodness knows when the rest of the farm buildings went up - probably in the late 19th or early 20th century. So, this story of the place moves on to recent history and how it was only 60 years ago.

Second, it is also a story of a small and fairly self reliant country community, where the last of the old Victorian values were still hanging on. We were a mile and a half from the nearest bus and the nearest town (Rochford) was two miles away, and so the farm had to have cottages for its workers to be close to where they worked. Father was the only one with a car, so everybody else walked or went by bicycle. The men had their own plots of land by their cottages to grow their own vegetables, and I dare say the odd rabbit and hare were taken. This relative remoteness meant that there was an underlying reliance on each other, and there was a feeling of permanence in this arrangement; each of the men with cottages knew that they had them for as long as they were working, and for their retirement after that. But you cannot ignore that it was still a structured society, where people were aware of their place and, while generally comfortable with it, could not easily get out and improve themselves. The established social structure meant that we were friendly with Dennis Brown, the local JP and Deputy Lieutenant for the county, who lived a mile or so away, but we did not go to tea there. We were tenant farmers, albeit fairly substantial ones, and Father was Church Warden at Sutton Church, as was Mother after him. However, the men went to their chapel at the end of the drive. But we all met together at the church for the annual Harvest Festival. At home, Adri (the au pair) ate with the family, but Beryl (who came in to help with the cooking and the house work) did not. She had her meals in the kitchen. And so on.

All that is now gone. The farm has been taken in hand by the Tabor Estates, and is part of a farming unit of 2000 acres or more. Nobody who works at Butlers lives there. The house now has a Tabor family living happily in it. Some of the cottages are let out, and Cadges cottage is home to an art club. The chitting shed houses a vintage car repair business, the yards are used as livery stables to house horses owned by people in the nearby towns. The men's chapel houses a small business. There is unused space elsewhere as there are no longer any cows or farm horses. Even the old stables have been pulled down. So it is part of a different regime, and there is plenty of life there, but it is a very different life.

Martin Edgar, August 2013.

12. EDITORIAL POSTSCRIPT

We had some email correspondence with Martin Edgar prior to the publication of this magnum opus article.

The email correspondence is reproduced here in full as it contains some relevant observations on the text such as clarification of some characters and text that was put in by Martin for family consumption.

Please note that the earliest email is at the bottom.

On 27/08/18 13:01, Martin Edgar wrote:

Thanks, Bob,

Have a nice time in France - and don't apologise for any time taken to finalise things. It took me at least five years to get round to putting the thing in the public domain! So don't hold your breath for the Ruth Cadge stuff either...

Cheers, Martin

On 27/08/2018 11:57, RDCA Bob wrote:

Thank you Martin,

We note the typo - brought about by us not proofreading our text on the website carefully enough (this we had created using an OCR facility on the internet to scan your paper copy, thus saving us the trouble of a lot of typing). Also, thank you for the clarifications and additional information.

We would appreciate Ruth Cadge's notes or your "bound up" version of them. If you do send us one or the other please leave the pages unbound as we will have to break them up to scan them and then to convert them to computer text for the site.

I think when we come to publish the article I'll split it up into chapters, each corresponding to the section headings of your original. There will be links between them so readers can move around easily. This way the material is easier on the eye and anyone leaving comments will have them associated with the relevant part of the text rather than all comments being put at the bottom of what is truly a magnum opus.

We are shortly leaving France and coming back to the UK slowly, expecting to get back to UK around about 12th September. I hope you don't mind us delaying publication until then. What I'll do is leave the existing article in place, with the same link you already have, and make minor alterations to it, such as the above typo, and then do the splitting up for publication shortly after I return.

Regards, Bob Stephen

On 26/08/18 16:35, Martin Edgar wrote:

You both have done a super job. A minor typo is that the neighbour at Paglesham was "Perry" - not "Peny". You can see a likeness of Mr Perry in the Southend Standard cartoon of the folks who ran Rochford market.

Furniture, and Rupert and Liz. The various remarks about items of furniture are in there because the piece was originally written in response to a half dropped remark of my nephew that he wanted his kids to know where their roots came from. So I wrote it up and circulated it round the family. It seemed appropriate also to tell them where the various bits and pieces we gave away on downsizing actually originated from. Personally, I think they distract from the general thread of the story, and I would edit them all out; but up to you!

In answer to your question, Rupert is my nephew, son of youngest brother Miles. Liz is the widow of my elder brother Robert. Do you need any more? I don't think either fit in the story, as Rupert was born after the story ends, and Liz married Robert in Rhodesia, where Robert went in his early 20s to make the rest of his life - an altogether different story.

The Cadges. The original Cadge - he of the bow legs - was William, and you have the pic of him and Mrs Cadge sitting in the drawing room of Butlers, having just been up to the Essex Show to receive his medal from the Queen Mum for 50 years agricultural service. He and Mrs had four sons (at least) - Walter (who became Foreman), Charlie (who became Head Tractor Driver) and a further two who died in the War.

Incidentally, my sister has just given me a copy of notes - about 20 pages, so more perhaps a rough memoir - by Ruth Cadge, who was Charlie's wife, which is the view from the other end of the telescope. Am minded to add a short forward, and bind it up as "Butlers - The View from the Cottages". Do you want a copy?

I have had a thought about the way things have changed. In a way it can be summed up by the fact that in the 40s and 50s the farm was run by Father and a staff of 13 in total, most of whom lived on site in the farm cottages with their families, kids and all. And it was a fairly self contained society as you have observed, being relatively cut off (two miles to the nearest town is quite a lot if you have to walk it). When Bill retired in the 90s, he ran the place with himself and one, with no animals and contract ploughing, contract seeding and contract harvesting. The people mostly seen around Butlers are now essentially commuters in, who run the various ventures taking place in the farm buildings. The flight from the country has taken place.

Best wishes, Martin

On 25/08/2018 18:51, RDCA Bob wrote:

Hello Martin,

After a bit of work your draft article is finally here:

http://www.rochforddistricthistory.org.uk/page.aspx?id=452

This is not yet published to the general public and sits in an inaccessible part of the RDCA site (now published and visible via above link or link in site Sutton category).

Some observations:

We have entered all your text. Please note that we have taken small liberties with it in a few places but in general it is exactly as you sent to us. We liked it a lot.

The photos have been cut up and distributed throughout the text. There are 17 in total. Note that for technical reasons we have had to change the shape of the photos to be landscape rather than portrait, so this means that legs etc are taken off and some of your composites have had to be chopped up. We have placed the photos where they seem relevant but we may have misplaced some: feel free to suggest repositioning or multiple placement of any of the 17 images as this is simple to do.

A couple of questions:

Rupert and Liz who have items of furniture - how do they fit into the story?

Is it William or Walter Cadge or are they separate persons? If separate, we need to offer an explanation in the text to avoid people thinking there is a misprint.

Regards, Bob Stephen (and Sue Horncastle who has helped with the text and layouts)